High Seas: The Last Frontier for Oceans Management

Charlotte de Fontaubert, Ph.D.

The high seas are open ocean and deep-sea areas that lie beyond

national jurisdiction, covering more than a third of the Earth's

surface. Despite their extensive nature, these areas remain woefully

understudied and misunderstood. Until recent decades it was widely

assumed that below a depth of a few thousand meters, life was almost

impossible and mostly irrelevant.

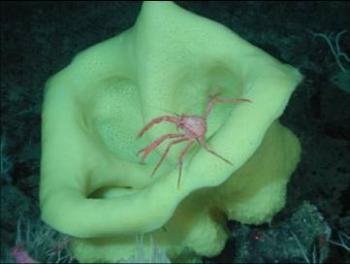

Fly-trap anemone (Family Hormathiidae)

on the slope of the

Davidson Seamount (1874 meters depth)

Photo courtesy of NOAA/MBARI

Introduction

Not surprisingly, we are far more familiar with coastal processes that more directly affect humans and occur in close proximity to human communities than we are with the biology of the abyssal plain. What is surprising, however, is how little attention the high seas have received, even with recent and spectacular scientific discoveries about their diverse webs of life.

Thus, while recent scientific progress has significantly filled knowledge gaps, management and policy have not kept pace with science and efforts to manage resources on the high seas have been largely inadequate. In fact, we have only been spurred to address the issue of high seas management because human activities have indeed started to have a visible and noticeable impact on these resources. In this respect, our attention to the high seas follows a lamentable pattern, where we only start paying mind to our natural resources once we start fearing their loss. As our excessive overuse of marine resources has proceeded ever seaward, so the threats to the high seas have mounted.

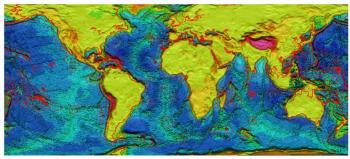

Fig.1 High-seas are all those areas beyond Exclusive Economic Zone

(or territorial sea limits where EEZs do not exist), both marked in red.

Source: WWF/IUCN, 2001

What, exactly, are the high seas?

One of the difficulties in dealing with the high seas is that even the concept of high seas is poorly understood. The accepted definition is more legal than biological in nature - though obviously their ecology is of considerable importance. Under the legal regime set up by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which was adopted in 1982 and is commonly referred to as a constitution for the oceans, coastal States are responsible for the management of marine resources within their coastal waters, broadlydefined as an area that extends from the coastline to 200 nautical miles offshore.1 This is particularly important because coastal States could, theoretically at least, control and impose limits on exploitation of resources within their zone of jurisdiction.2 No single entity, however, has such power on the high seas and the regime that prevails is one of freedom of exploitation. This freedom is not absolute but is mainly constrained by the rights of other States to share in the exploitation of resources. What is sorely missing is an emphasis on conservation, or, at the very least, sustainability.

However, legal regimes tend not to be static in nature but rather evolve, usually as the level of pressure on resources or potential for conflict increases. Throughout the history of marine exploitation, new conservation and management measures have been adopted, often after lengthy and sometimes acrimonious negotiations. In general this occurs after unfettered exploitation has led to depletion of the resources. Historically, exploitation of living and non-living marine resources first occurred in the coastal zone, where exploitation is facilitated by the fact that living resources tend to aggregate in shallower waters over the continental shelf. Exploitation then moved further offshore, all the way to the high seas, in part because because coastal resources became over-exploited, and in part because new technologies allowed ever-increasing access to remote areas (remote being not only distance from shore, but also vertical distance - or depth - from the ocean's surface). In some cases, over-exploitation has already started to have dramatic impacts on ecosystems of the open oceans, and evidence suggests that entire seamount ecosystems have already been destroyed by some trawling operations.

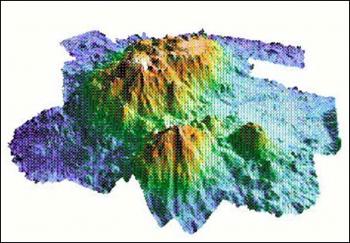

From an oceanographic standpoint, the high seas are characterized by much greater depths than those found over the continental shelf (which usually rarely exceeds 100 m. in depth), starting with the continental slope (150-3000 m.) and leading to the continental rise, which extends to the abyssal plan (around 6000 m.) At the level of the abyssal plain, trenches and seamounts occur, with trenches averaging depths around 3000-4000 m. from the abyssal plain and reaching more than 10000 m. from the surface in the case of the Mariannas Trench. In contrast, seamounts rise up from the abyssal plain, never breaking the surface but providing shallower zones more hospitable to marine life. Because they are home to a high level of biodiversity, seamounts have been the first ecosystems targeted for exploitation and the usual cycle of exploitation-over-exploitation-destruction has already begun. Perhaps not coincidentally, the only significant international conservation measures have been initiated around the protection of the very same seamounts, though these conservation measures remain very timid in nature and widely opposed by those States whose fleets engage in destructive fishing. But, inadequate as it is, this effort to conserve seamounts is the only one that attempts to protect resources of the high seas in earnest.

Patton Seamount located in the Gulf of Alaska - 10,000 feet tall and 20 miles wide.

Bathymetric map courtesy of NOAA,

www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov

Why should we care about the high seas?

In a joint report published in 2001, the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the World Conservation Union (IUCN) shone light on a number of habitats and features of the high seas that were largely being overlooked by the conservation community but that deserved further scrutiny and protection. These features were prioritized because a) they contain particularly fragile and important biodiversity and b) because they are under direct threat, whether in the short or longer term, from human exploitation. They include:

- Hydrothermal vents, which are areas of very high biodiversity and under actual threat from scientific study

- Deep-sea trenches, few of which are found on the high seas but under threat from biogenetic exploitation and as a repository for hazardous waste

- Polymetallic nodules, for which full economic exploitation may be less than 20 years removed

- Gas hydrates, which are under threat from direct and potential biogenetic exploitation

- Seabirds, which are mostly threatened as they are caught as bycatch in extensive long-line fishing operations

- Transboundary fish stocks, some of which are heavily exploited and threatened with depletion

- Seamounts, some of which have already been rampaged by bottom trawling

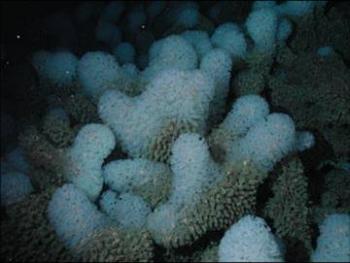

- Deep sea "coral reefs", which are just as fragile as their coastal counterparts and are threatened by destructive fishing methods and deep-water oil exploitation

- Cold seeps and pockmarks, which are under potential threat from biogenetic exploitation and deep water oil exploitation

- Submarine canyons, where many species are targeted by direct exploitation and where terrestrial pollutants can have a direct influence; and

- Cetaceans, which are under siege from direct (whaling) and indirect (ship collision, pollution, disruptive of food web in the Southern Ocean) threats.

All these ecosystems, marine features, and taxonomic groups are under very real threat, either because they are found only on the high seas and are inherently vulnerable, or because destructive practices are being used to exploit their resources.3 Most worrisome of all, however, is that we do not really know how much exploitation is actually taking place and what habitats and features are destroyed before they are even identified. In the case of seamounts, for instance, scientific research to date has shown a very high level of endemism, where some species can only be found on a given seamount. We already know that some seamounts have already been completely destroyed so the odds are very high that we have already lost species of which we were not even aware.

The resemblance between these deep-sea coral reefs and their coastal,

shallow-watercounterparts can be striking.

Photo courtesy of NOAA/MBARI.

What can we do about the high seas?

Looking back at the past 50 years of marine resource use, we have come full circle from discovery of resources to their exploitation, over-exploitation, depletion, and in a few cases, recovery. Thus the causes for optimism may be limited. However, a shift is discernible in the last 20-30 years, where decision makers at all levels have become more aware of the responsibility that is theirs and have started taking new approaches to resource management. This shift, which continues to occur very slowly, involves the embodiment of the two pillars of sustainable development: the ecosystem approach and the precautionary principle. Nowhere is the application of these two principles more called for than on the high seas, where we still have a chance to take preventive measures to avoid the boom and bust cycles of exploitation that can otherwise be expected. Likewise, our understanding of ecological processes has increased exponentially, and though there are too many areas of the high seas where our knowledge remains limited, we know enough to understand that destructive activities in one area will likely have impacts in other areas. We also know by now that allowing unfettered exploitation is extremely risky and will more than likely lead to the destruction of valuable resources, some of which may remain undiscovered to this day but may prove invaluable to humanity in the future.

The issue that remains is how we can best incorporate the ecosystem approach and the precautionary principle to the management of resources on the high seas. These are commonly used, though sometimes misused or poorly defined terms. Ecosystem management has many definitions; one example is "ecosystem management looks at all the links among living and nonliving resources rather than considering single species in isolation... It reflects the relationship among all ecosystem components, including human and nonhuman species, and the environments in which they live. This system considers human activities, their benefits, and their potential impacts within the context of the broader biological or physical environment."4 Of course such a management approach makes sense for the high seas, but questions remain on how to implement such an approach.

The precautionary principle also applies to the high seas, since so little is known about them. The principle may be defined as: "not allowing an activity if the impacts of such activity are unknown." In effect, applying the precautionary principle requires reversing the burden of proof, where the party that wants to carry out a new activity is required to show that this activity will not have undue and deleterious impacts on the resources impacted. Consequently, exploitation of resources on the high seas ought not be permitted until the impacts of this exploitation are understood and deemed acceptable.

With regards to the high seas, these principles might lead us to ask: Is it enough to stop any new exploitation project as it arises? And if so, how do we know when new exploitation commences? And what of the issue of jurisdiction - who, in practice, has the actual authority to prevent, or even stop, destructive activities as they occur? The answer to many of these questions may well be political in nature, and unfortunately it is not yet apparent that all States currently have the will to stop their nationals from engaging in such activities. Some, for instance, have a track record of encouraging their fleets to engage in pulse fishing, where fleets migrate over huge distances in search of new, unexploited fisheries because they have destroyed the ones in which they had been previously engaged. Other more conservation-minded States, however, may attempt to prevent the movement of these fleets to unexploited areas of the high seas through the designation of marine protected areas (MPAs).

The potential for marine protected areas on the high seas

The issue of high seas MPAs (HSMPAs) remains a controversial one but the idea is gradually becoming more accepted and is being endorsed in different fora (see for instance, De Fontaubert, 2002). While HSMPAs have not yet been endorsed in legally-binding treaties, their implementation is nowhere prohibited by international law. One of the fundamental tenets of international law, however, provides that no State will be bound by new international measures unless it is willing to do so. Consequently, the push for HSMPAs has come from a small, but growing number of States and, as of June 2006, is still opposed by others whose nationals are engaged in fishing on the high seas. In a related move, the UN General Assembly put forward a statement in a resolution on sustainable fisheries that calls for a review of progress on actions by States and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations or arrangements to address the effect of destructive fishing practices, including bottom trawling, on vulnerable marine ecosystems.5 This was catalyzed in part by a statement put out by the UN Open-Ended Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea (UNICPOLOS) in June of 2005, calling on countries to protect deep sea ecosystems. Some coastal States have shown particular leadership in moving high seas protections forward. Palau, for instance, originally tabled the proposal to create a moratorium on deep seabed trawling.

MPAs can vary greatly in shape, size and the level of restriction they afford - sometimes they merely ban a given activity. In an interesting move, the nations of the European Union recently declared the entire body of Mediterranean high seas at depths over 1000 meters off limits to trawling. Though this may seem insignificant, it should be remembered that the vast majority of Mediterranean waters are high seas, since the riparian countries have not declared 200 nautical mile EEZs and their jurisdiction only typically extends to 12 n.m. offshore. Because the Mediterranean is deep in many places, and because the threat from bottom trawling was recognized, this step by the EU can be thought of as an important first step toward comprehensive high seas protection of the Mediterranean.

The Mediterranean is also the site of one of the only multinationally-designated high seas marine protected areas. In 1991, a grassroots effort originating in Italy stimulated a proposal for the establishment of a large marine area to protect cetacean populations found in a portion of the national waters of France, Italy and Monaco, and in the adjacent international waters. This concept eventually led to a tripartite international agreement to create the "International Sanctuary for the Protection of Mediterranean Marine Mammals", also known as the "Pelagos Sanctuary". The impetus for the Sanctuary came from three directions: (a) recently acquired knowledge of the presence of important populations of cetaceans in the area; (b) awareness of the existence of serious threats to such populations; and (c) lack of existing legal instruments for the protection of the Mediterranean high seas, where most of these populations' habitats lie.6 However, this high seas MPA is different from most HSMPAs, since the designation largely concerns the water column and the organisms within it, not the benthos.

Moving forward

There are pressing needs to promote high seas protection further, as an uncontrolled and destructive attitude towards access and exploitation continues to prevail on the part of certain States. The situation, however, is not static, and in this respect, civil society has been instrumental in keeping government attention focused on the high seas. The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, for instance, was founded with the intent of evaluating the impacts of human activity on the hitherto ignored seafloor of the high seas and promoting conservation measures there.7 New alliances can be built and political opinion changed as more scientific discoveries are made.

Renewed efforts to protect the high seas echo past campaigns that have been fought and won to protect resources that were under dire straits. The international campaign to ban drift-nets, for instance, brought together environmental NGOs and some concerned States to overcome the resistance of those States that had benefited from their deployment. The scientific information on the devastating impacts of these nets that extend over tens of miles was available and understood, but action to restrict, and eventually ban them, only became possible once the public was informed - and became outraged. The most conservative legal scholars had long argued that strong conservation measures could not be taken on the high seas, and that international law and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea did not allow for any restriction on the Freedom of the Seas. Once the political winds started to turn, however, States revealed that they could actually abide by the restrictions that were necessary to preserve some species, even if those species were found on the high seas.

The situation today is not very different, a handful of States stands to benefit from overexploitation while the world at large will suffer the destruction of some high seas ecosystems, still poorly known yet nevertheless essential. The same argument is being put forward as in the case of the ban on drift-nets: that international law does not provide for the designation of high seas MPAs. The opposite, however is also true, in that no instrument of international law actually prohibits the designation of high seas MPAs, so long as States are willing to be bound by such restrictions. In view of the preponderance of the precautionary principle, we can argue that the high seas can and must be protected, and that those who want to pursue unfettered exploitation need to bring forth the impossible proof that their activities will not destroy entire ecosystems. Science calls for the adoption of strong conservation measures, including MPAs where appropriate, and international law allows for their designation.

Progress is also being achieved in the understanding and implementation of the ecosystem approach, including within the framework of the United Nations Open-ended Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea. This process is convened annually and provides a forum where the most pressing issues relating to oceans management can be discussed in a relatively open fashion. In contrast to other, more formal, intergovernmental processes, for instance, participation by NGOs and civil society is relatively open and negotiators are apprised of the latest scientific research. From June 12-16, 2006, the seventh meeting of this process was convened at UN Headquarters in New York and focused specifically on the implementation of the ecosystem approach, including on the high seas.8 While no legally-binding decisions were taken, an honest discussion of Regional Fisheries Management Organizations and the potential for networks of marine protected areas took place and the result of these discussions will be forwarded to the UN General Assembly in October and November 2006.

The political stage is thus well in place, though what appears to be lacking is the political momentum that will allow to put pressure on recalcitrant States. We know those States have been convinced in the past and that the scientific evidence is too overwhelming to be ignored. The question remains of knowing how such political pressure can be applied, how we can create the same feeling of outrage at the senseless destruction that has already begun on the high seas. Only with the answer to this question can we avoid repeating our mistakes of the past 50 years and truly protect some of our last areas of wilderness.

New species are constantly being discovered as our understanding

and knowledge of the high seas increases but we probably

have barely scratched the surface of what lies beneath.

Photo courtesy of NOAA/MBARI

Endnotes

1 As a treaty negotiated over decades, the Convention is particularly complex and in some instances, the limit can extend up to 350 nautical miles. For more details on the Law of the Sea regime, see De Fontaubert and Lutchman, 2003.

2 Sadly, the fact that a state entity has jurisdictional rights does little to ensure sustainability in practice. According to the latest UN figures, 70% of fisheries worldwide are exploited at full capacity, are over-exploited or recovering from over-exploitation. Concurrently, 90% of fish caught are harvested in coastal waters so coastal states are doing more than their fair share in over-exploiting resources and the fisheries crisis cannot be attributed to jurisdictional uncertainty.

3 More details on the value of these habitats and features and the threats under which they are can be found in the full report published by WWF and IUCN at http://www.iucn.org/themes/marine/pdf/highseas.pdf

4 US Commission on Ocean Policy. 2004. An Ocean Blueprint for the 21st Century. Washington, DC

5 UN General Assembly Resolution, Paragraph 73 and 74 of A/RES/60/31

6 Notarbartolo-di-Sciara,G., T. Agardy, D. Hyrenbach, T. Scovazzi , P. Van Klaveren. The Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean marine mammals. In prep

7 See http://www.savethehighseas.org

8 For a thorough summary of this process, see the latest issue of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin at http://www.iisd.ca/download/pdf/enb2531e.pdf.

References and Further Reading

de Fontaubert, A.C. and I. Lutchman. 2003. Achieving Sustainable Fisheries: Implementing the New International Legal Regime. IUCN, Gland and Cambridge.

de Fontaubert, A.C. 2003. Protecting Marine Biodiversity on the High Seas: the Next Frontier of International Law. Presentation to the Workshop on the Governance of High Seas Biodiversity Convention, Cairns, Australia

Kimball, L. 2005. The International Legal Regime of the High Seas and the Seabed Beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction and Options for Cooperation for the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in Marine Areas Beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Technical Series no. 19, 64 pages. Available for download at: http://www.iucn.org/themes/marine/pdf/cbd-ts-19.pdf

WWF/IUCN (2001). The status of natural resources on the high-seas. WWF/IUCN,

Gland, Switzerland. Available for download at: http://www.iucn.org/themes/marine/pdf/highseas.pdf

For more information on efforts to limit illegal fishing on the high seas, see: http://www.high-seas.org/

For more information on seamounts, see:

http://www.asoc.org/what_seamounts.htm

http://seamounts.sdsc.edu/